Aperture plays a key role in every exposure, along with Shutterspeed and ISO. If you need a quick refresher on how these three settings interact, check out Understanding the Exposure Triangle→ .

But what is aperture?

The textbook answer is "the amount of light you let pass through your lens." You can control this adjustable opening insight the lens through either a ring on your lens or a dial on your camera.

Let's break that down in more practical terms. Pretend you're nearsighted and struggling to read a sign in the distance. What do you do?

You squint.

Squinting and stopping down your aperture (say from f/1.4 → f/8) do the same things: they let in less light and increase what's called depth of field—the amount of your image that is appears in sharp focus.

What the f/

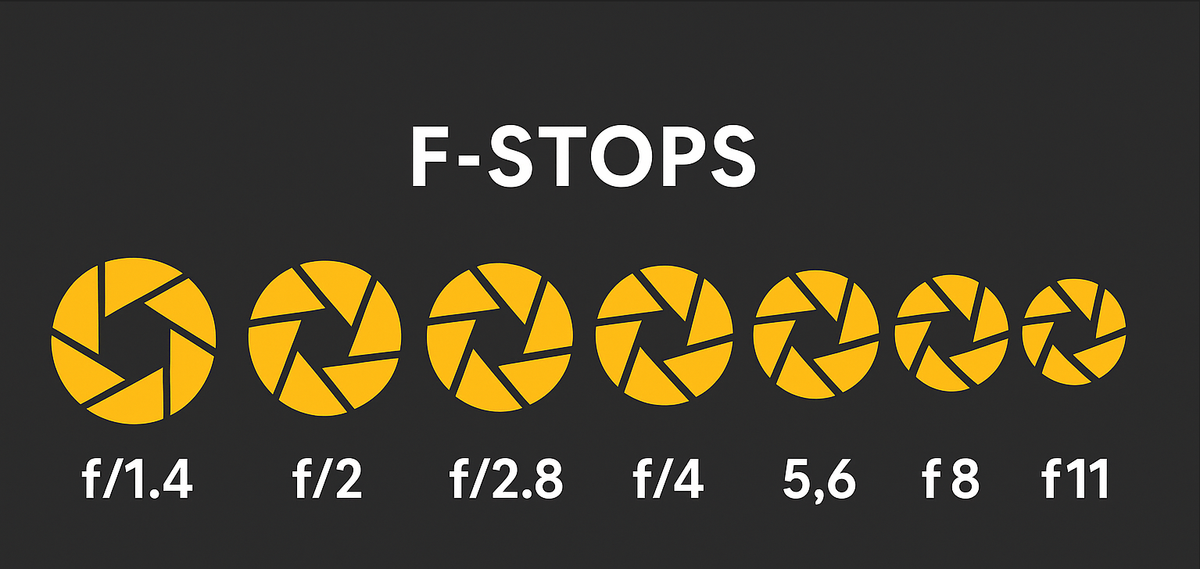

Aperture is measured in f-stops.

Generally, a smaller number means a larger opening and a larger number means a smaller opening. Those are quite literally the only two things you really need to know about aperture & f-stops.

An f-stop is a ratio between your lens’s focal length and the diameter of the aperture.

A 50mm lens at f/2 means the opening is 25mm wide (50 ÷ 2).

At f/4, it’s 12.5mm wide — half the size, half the light.

So smaller f-number → bigger hole → more light.

Larger f-number → smaller hole → less light.

Simple math, confusing naming.

You’ll also hear photographers call wide apertures “fast.” That’s because they let in more light, allowing for faster shutter speeds.

When someone says a lens is “fast,” it just means it has a wider maximum aperture — typically f/2.8 or lower.

Put another way: the faster the lens, the higher the price tag

Depth of Field and Aperture

If you’ve just bought your first camera kit — say, a body with a 24–105mm f/4 zoom — and wonder why your photos don’t look “as professional,” your aperture is a big part of that.

It's a bit like comparing a high end sports car to a minivan. Both get you where you're going, but one does it with considerably more style.

That "style" is rendered in photos as depth of field, and is typically used to isolate a subject on a blurry background. The amount of "bokeh" in an image can sometime transform a droll scene into something more epic and cinematic.

It's literally Japanese for "blurry." But definitely use this term to sound smart to non-photographers. Most people pronounce it "bow-kuh."

While faster apertures generally have shallower depth of field (less of the frame is in focus), you don't necessarily have to shoot wide open (maximum aperture) to get the best effect. In fact, you'll notice over time that your images render sharper with better color reproduction when you stop them down a bit. Let's look at some practical examples.

This photo was taken with a portrait lens (a longer focal length, aka "telephoto" lens, 135mm) from ~15 feet away. This particular lens's max aperture is f/1.8 (that's big premium pro-grade stuff), but this image was stopped down to f/5.6. There's STILL a stunning amount of bokeh, but the subject is rendered in focus from front to back.

This image was shot on a "normal" lens (just means the perspective looks “right” to the human eye), but was shot at f/3.5 (max possible aperture was f/1.2).

There can be some debate as to when a lens transitions from one type to another, but there are three primary types of lenses. The rough categorizations are:

- Wide-angle: capture broad perspective, but tend to exaggerate space and subjects appear smaller than they are in frame. 24mm is a common example, but can go even wider like 10mm or fisheye. These are workhorse lenses for landscape, street, and architecture photographers.

- Normal: render a perspective that looks correct to us because the focal length is similar to the diagonal measurement of the sensor. These are typically anything between 35mm and 50mm and widely used by all types of photographers. In fact, it’s a common opinion that learning photography with a 50mm lens is one of the best and least expensive ways to start out able to produce professional level images in terms of optical quality.

- Telephoto: Compress space and can make objects in the distance look larger. You know how the moon or mountains look unnaturally big in movies sometimes? Those scenes were likely shot on longer lenses, like 85mm or really anything longer than around 60mm. These are ideal for portrait photographers, as they have a flattering effect for most faces.

These two examples show what shallow depth of field looks like, and if you're looking to shoot more portraits you're likely going to want to buy a lot of fast lenses. They also show the effect focal length can have on depth of field. In general, lenses with longer focal lengths can produce more pleasing bokeh than wider angle lenses. For example, a 24mm at f/2.8 will still have a much wider depth of field than a 135mm lens at f/2.8.

Let's look at a different style of image: a landscape. Generally, you want landscapes to be in focus throughout the frame. That means you'll probably want to stop down to a smaller aperture, teypically anywhere between f/8 and f/22 (or however high your lens's f-stop goes).

This image was shot with the same 50mm lens as the portrait above. So why is the depth of field so different?

Well, there are two reasons:

- Camera-to-Subject-to-background distance → Generally, if the distance between the camera and subject is small but the distance between the subject and the background is larger, depth of field will be shallower. Inverse is also true.

- Aperture setting → this was stopped down to f/16

Closing Thoughts

Aperture is one of photography's most powerful creative tools. It controls not just how bright your photo is, but also how it feels. Once you start to see depth of field as part of your visual vocabulary, you'll use it intentionally—not just technically.

But above all, get your camera and go shoot something. Set your camera to Aperture priority if that's helpful for you to only have to think about one setting at a time. Shoot wide open. Stop down. Take note of how the other settings need to adapt to compensate.

Shoot the same subject at f/2.8 (or however fast you can), f/5.6, and f/11. Notice how the focus and bckground separation change. That's aperture in action.